The Moon Landing Hoax Theory Started as a Joke

In questi giorni di celebrazioni dei cinquant'anni dallo sbarco sulla luna, si sono dette molte cose e rievocati anche i molti dubbi. Molto spesso, la personalità degli astronauti dell'Apollo, è stata descritta come introversa, sfuggevole e inspiegabilmente riservata. Molti luna-complottisti, infatti, hanno cominciato a screditare le missioni Apollo, proprio considerando negativo e alquanto strano questo fatto.

I teorici del complotto, infatti, ritengono che l'atteggiamento chiuso e fin troppo riservato degli astronauti che camminarono sulla Luna, ma anche quello delle loro famiglie, sia da attribuirsi al fatto che essi temano un confronto troppo ravvicinato con il pubblico, che ne possa facilmente evidenziare lo stress psicologico, maturato dall'essere stati protagonisti di una beffa colossale. Darryn King ha una sua storia sull'argomento ben documentata, volentieri la pubblichiamo

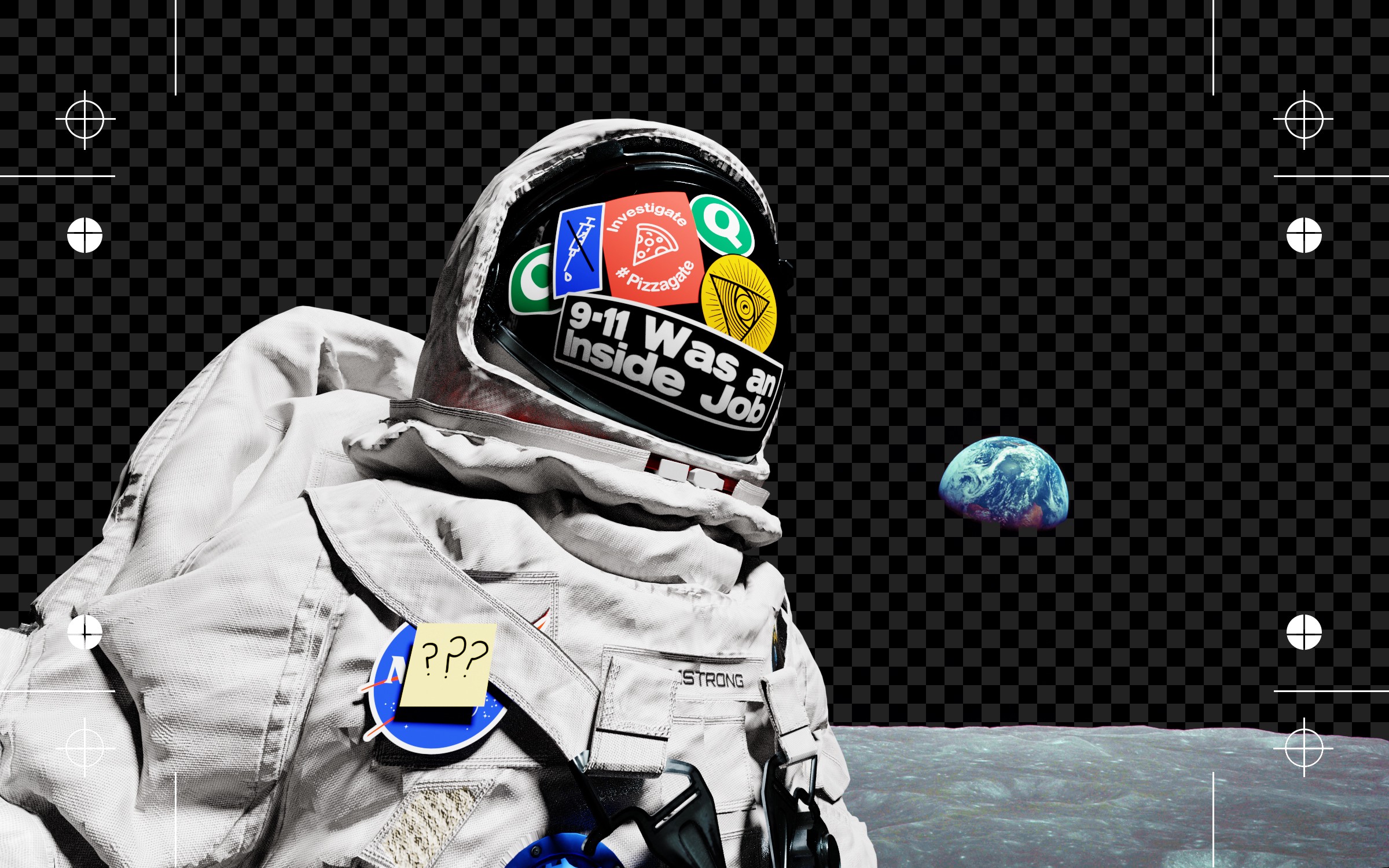

How a freelance writer sowed doubts

about the Apollo mission — now 50 years old — laying the groundwork

for 9/11 truthers, birtherism, Pizzagate, and QAnon

In December 1969, NASA’s public affairs chief, Julian Scheer, made a presentation to a group of aviation experts gathered in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. Speaking six months after an estimated 650 million people watched a televised feed of the first Apollo moon landing, Scheer showed a series of films depicting cavorting astronauts and scientific equipment on what appeared to be a lunar landscape. The footage, Scheer revealed, was entirely terrestrial, shot during simulation exercises at NASA’s space-training facilities, including a rock quarry in Michigan. “You can really fake things on the ground — almost to the point of deception,” Scheer said, before inviting his audience to “come to your own decision about whether or not man actually did walk on the moon.”

Scheer’s talk was a goof, a winking thought experiment prepared for the 10th annual meeting of the Man Will Never Fly Memorial Society. The society, a satirical social club “dedicated to the principle that two Wrights made a wrong at Kitty Hawk,” comprised a group of hard-drinking pilots and airline executives who liked their booze served with irony and vice versa. (Motto: “Birds fly, men drink.”)

Scheer’s absurdist presentation was a sign of just how unthinkable it was to suppose that the moon landing was an elaborate hoax that had been conjured at the highest levels of the U.S. government. At the time, according to the New York Times, the notion was mostly confined to “a few stool-warmers in Chicago.” Within a decade, however, the idea would gain so much traction that NASA would find itself compelled to issue an earnest, and somewhat aggravated, fact sheet to debunk the conspiracy theory. “” the 1977 document began. “Yes. Astronauts did land on the Moon.”

The unlikely instigator of that reversal was a vagabond writer named Bill Kaysing. A free spirit with a healthy tan and the winning smile of someone who had it all figured out, Kaysing seems a peculiar figurehead for the movement he set in motion. But it was his 1976 book We Never Went to the Moon: America’s Thirty Billion Dollar Swindle and the wide-eyed media coverage that followed it that turned barroom bunkum into a national phenomenon. Long before anyone worried about deepfakes or A.I. video manipulation, Kaysing warned his readers that they couldn’t trust the televised evidence they’d seen with their own eyes.

What’s even more improbable is that, as Kaysing himself admitted, the moon-hoax conspiracy theory itself began as a hoax. They called him Wild Bill.

Born in Chicago on July 31, 1922, William Kaysing grew up in South Pasadena, California. His childhood, he later said, was like something out of Huckleberry Finn. He had a paper route, went rafting on the Arroyo Seco River, and ate apples he found behind the grocery store.

He couldn’t wait to leave home. His violent and abusive father died when he was nine; his mother was emotionally absent; and he had very little to do with his older brother, who would later become an aeronautical engineer. Fresh out of high school at 17 — and after a single week of working in a furniture factory when he decided it wasn’t for him — he made his way to San Pedro, where he got a job on a fishing boat and got paid in fish.

After serving as a Navy midshipman in the war, Kaysing obtained a B.A. in English literature, married, and had two daughters. He worked briefly as a salesman, an insurance claims examiner, and a cabinetmaker until, in February 1956, he got a job as a technical writer at Rocketdyne, a division of North American Aviation that developed NASA’s rocket engine technology.

Kaysing suffered chronic anxiety, which, over time, turned into full-blown disillusionment with modern life. He got rid of the family television set after a particularly violent episode of Gunsmoke, despite the protests of his daughters. He trashed his radio and canceled his newspaper subscription. He railed against the “blandishments of Madison Avenue” and the “lure of supermarkets” and other “insidiously engendered wants.”

Kaysing quit his job at Rocketdyne in 1963, years before he would have observed anything that would qualify as insight into the company’s contribution to the Apollo missions. He bought a trailer with bunk beds for the girls and embarked on a “year-round vacation.” Before long, he parted ways with his wife and family too.

For the better part of the next decade, Kaysing had no fixed address. He foraged for food and picked up odd jobs — freelance writing, fruit-picking, security, and selling dentistry equipment by mail-order. Then, in 1971, he persuaded Straight Arrow Press, which published Rolling Stone, to put out his first book, The Ex-Urbanite’s Complete & Illustrated Easy-Does-It First-Time Farmer’s Guide. Kaysing finished the manuscript in a month, dispensing wisdom on everything from acorns to yurts in his homespun writing style, with epigraphs quoting William Faulkner and the Old Testament and photographs of hippie layabouts provided by the 1960s-chronicling Rolling Stone photojournalist Robert Altman.

“Why don’t you write something outrageous? Like, we never went to the moon?”

Kaysing was passionate about teaching readers how to live healthful, low-cost, and adventurous lives. In between headings like “Where to pick your fresh foods for free,” “What you should know about sugar,” and “Should you get a cow?” he composed lyrical passages about the exquisite pleasures of fresh air, wildflowers, geothermal springs, and motorcycling through the desert.

More books followed, with more contributions from Altman and Rolling Stone designer Jon Goodchild: The Robin Hood Handbook, Great Hot Springs of the West, Dollar a Day Cookbook, and How to Live in the New America. Alongside practical advice on growing vegetables and making compost, a theme of social protest and a darker, more conspiratorial tone often came to the fore: “Enough people must rise up to oppose the injustices and inequities,” he wrote, “the outright tyranny and chicanery of the existing power structure.”

With their rambling, tax-evading lifestyle, Kaysing and his new wife and co-writer, Ruth, often came into contact with other social outsiders and dropouts. One was John Grant, a homeless heroin addict and Vietnam vet who bonded with Kaysing over a mutual contempt for the system. One day, Grant suggested that Kaysing could use his influence as a writer to undermine the government.

“Why don’t you write something outrageous?” he said, as Kaysing later in an unaired segment of an interview for the 2001 documentary, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Moon. “Like, we never went to the moon?”

Such doubts were not uncommon. In a widely reported, though far from scientific, 1970 survey, 1,721 U.S. citizens were asked, “Do you really, completely believe that the United States has actually landed men on the moon and returned them to earth again?” In one community in Washington, D.C., as many as 54% of respondents did not “really, completely believe.” As yet, though, there was no one making the case, in a sustained way, that the moon landing hadn’t occurred.

Kaysing was reluctant at first. He had intended his next project to be Eat Well on a Dollar a Day, a how-to guide packed with nutritional advice, money-saving hints, and wholesome recipes from around the world, including an entire chapter devoted to the excellence of the humble potato. But in August 1974, the same month as Richard Nixon’s forced resignation in the wake of the Watergate scandal and with the Vietnam War still raging, Kaysing signed a contract with Price, Stern, and Sloan, an L.A. publisher, to write a book of fiction called We Never Went to the Moon. Initially the book, like Julian Scheer’s presentation to the Man Will Never Fly banquet, was meant as a hoax. “We agreed,” he told an underground newspaper, the Los Angeles Free Press, “that it would be a spoof, a satire.”

In that 1975 article, Kaysing noted that he’d been inspired by Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 Cold War black comedy Dr. Strangelove and The Report from Iron Mountain, a cunning forgery of a suppressed government document published in 1967. In the book itself, he also cited the influence of Executive Action, the widely derided 1973 conspiracy thriller that fictionalized the assassination of John F. Kennedy and was so controversial that it was pulled from many theaters. As for the actual Apollo 11 broadcasts in 1969, Kaysing proudly claimed he hadn’t even bothered to watch those or paid much attention to news stories about them.

“Playing the devil’s advocate, I began to question every step of the various moon flights,” he told the newspaper. “I found myself wondering,” he also explained, “whether I was working on a hoax or whether I was actually becoming a technical detective. Little by little, the evidence seemed to build in the favor of the Apollo Project itself being a gigantic hoax.” By the time he completed the book, Kaysing’s original satirical intent had given way to a conviction that the moon landing was indeed a lie.

We Never Went to the Moon outlines the vague shape of the conspiracy theory as we know it today: the urgent political need to best the Soviet Union; the perceived optical anomalies in lunar photographs (“Stars? Where are the STARS?”); a subterranean soundstage in Nevada; and the involvement of Stanley Kubrick. (2001: A Space Odysseywas supposedly a cover, the Argo of its time.)

No shred of evidence was too small or insignificant for Kaysing to manipulate in support of his conclusion. The way the astronauts’ relatives sometimes referred to the “unreality” of events? That was because the events were unreal. The astronauts’ lengthy stay in quarantine after their return? They simply could not bear to face hordes of cheering people so soon after their deception. The fact that many Apollo astronauts ended up as well-paid corporate executives? That was their real reward for their moon “trip.” Buzz Aldrin’s post-mission nervous breakdown? The result of a guilty conscience.

And what about all those photographs and television transmissions? Easily faked. Obviously the astronauts should have made “some visible signal from the moon” instead — as if going out of their way to prove they were really on the moon had been the whole point.

The likelihood of a successful lunar mission, Kaysing reports, had been calculated at 0.017%. By whom and when and how, he never says. And yet he would repeat the figure without context for the rest of his life. Elsewhere in the book, with the same casual authority, he compares the various operations of Apollo 11 to “rolling nine sevens in a row” and claiming that, according to “statisticians,” a successful lunar descent was “beyond probability.”

The book’s centerpiece is a scenario that Kaysing dubs the ASP, or Apollo Simulation Project, a reimagining of how the awesome deception might have played out. In Kaysing’s version of the events, as the empty Apollo 11 rocket was lifting off, the Earth-bound astronauts were spirited to a simulation set. Once out of sight of the spectators and television cameras in Cape Canaveral, the rocket was simply rerouted, shut down, and jettisoned in the South Polar Sea. (Elsewhere in the book, Kaysing criticizes NASA for “cluttering up space” with jettisoned Apollo modules.)

The detailed moon set — “a tribute to the painstaking work of the simulators on an unlimited budget” — was built on a soundstage, codenamed Copernicus, in an underground cavern. The bunker was equipped with high-intensity lighting to imitate the glare of the sun as well as scale models of the Earth, sun, and moon. With Hollywood experts on hand, staging the astronauts’ lunar frolics was easy.

When Fox aired a documentary asking if we’d really landed on the moon, NASA issued a one-paragraph press release with the heading “Apollo: Yes, We Did.”

To simulate the splashdown, the Apollo 11 astronauts were picked up from a secret island near Honolulu, packed in the command module, and dropped by a cargo plane from a great height. Kaysing eventually discloses that the whole idea of the ASP, which is richly imagined if sketchily presented, is a “documentary fantasy,” a “best guess” — but not until the “summary” at the end of his book.

Perhaps the most bizarre section of We Never Went to the Moon is its fully illustrated travelogue on the heady delights of Nevada. “Clerks and secretaries for the ASP control center,” Kaysing writes beneath a full-page photograph of a cavorting, laughing woman in a bikini, “were recruited from Las Vegas casinos, which added to the general appeal of the location.” Most of the time, the astronauts were “free to wander about and play the slots.”

Kaysing wrote the book in Las Vegas, which might go some way toward explaining the advertorial tone and the glowing mentions of one establishment in particular. “MGM Grand Hotel, at right, is booked up solid for three years. Try the Dunes for a room.” (Come for the exposé of the scam of the century; stay for the advice that the “finest buffet in the world” is served on the 24th floor of the Dunes Hotel.)

More darkly, though Kaysing lacks anything resembling evidence to suggest it, he proposes that the accidental death of an Apollo safety inspector, Thomas Baron, in a car-train crash was a NASA hit job. In later interviews, he would add the crew of Apollo 1 to the list of potential whistleblowers that the space agency had allegedly murdered. These were grave and attention-grabbing accusations — offered up without a shred of real evidence.

The book culminates with a return to the theme that had long preoccupied Kaysing: Society was the real con all along. Years earlier, he writes, he realized that “my family and I were being swindled; that living a life style arranged by others was actually a very serious hoax.” The moon-landing conspiracy was not unique; in fact, Kaysing concludes, now back on familiar ground, the “real point” of his book is that “it is not the only hoax perpetrated by those in power for their own personal gain.”

Finally, Kaysing implores the reader to follow his example, quit the rat race, and “question everything and everyone.”

To ToKaysing’s surprise, the publisher rejected the manuscript. “I am afraid we disavow it,” the rejection letter read — not because it was a baseless conspiratorial fantasy, but because it was a mess. “You need to read it objectively and critically and perhaps ORGANIZE IT,” the letter went on. “As it is it wanders all over the landscape. Several interesting paragraphs but they don’t hold together. You’ve also wandered from third to first person. It needs a lot of work. You don’t really have a manuscript here — seemed more like random notes about what you would write about if you got around to it.”

In November 1975, before Kaysing found a new publisher, he mentioned We Never Went to the Moon to a staffer with the Zodiac News Service counterculture newspaper, which alluded to the book in its next issue. Kaysing’s thesis, all there in the authoritative title, caused a stir, and interview requests for print, radio, and television streamed in.

At least one radio talk show host cut Kaysing off mid-interview and accused him of “irresponsible journalism.” Others, however, perhaps deeming him self-evidently ridiculous, seemed perfectly happy to provide him a platform in exchange for readers and ratings and allowed him to outline his arguments untroubled by rebuttal or serious analysis. After Kaysing appeared on NBC’s popular late-night talk show Tomorrow with Tom Snyderin December 1975, the show’s producer wrote him, obviously pleased, “We have received a great deal of mail in response to your appearance.” And when NASA was approached for comment, by the Times and Democratnewspaper, they lamely admitted there were “many millions” around the world who shared Kaysing’s skepticism.

Kaysing did eventually find an interested publisher in Barry Reid, whose own books, The Paper Trip and How to Disappear in America, explained how to evade the draft, take on the identity of a dead person, and/or acquire a fake Social Security number. (Reid would be convicted of mail fraud by the end of the decade.) But, by the time We Never Went to the Moon was published in 1976, no one needed to read it — Kaysing’s ideas were out there.

Bill Kaysing was the unlikeliest but most effective single conspiracy-monger of the twentieth century.

The media attention appealed to Kaysing’s crusading spirit. He was particularly proud of a 1981 appearance on People Are Talking, a talk show co-hosted by Oprah Winfrey, when he appeared between a segment featuring a creation “scientist” decrying the teaching of evolution in schools and a discussion on the topic “Who’s looking out for men’s rights?” He was similarly pleased about the 4,000-word article in Wired in 1994 that considerately laid out his case.

And if he enjoyed the spotlight, he was positively thrilled to think he’d ruffled feathers and made enemies in high places. One radio appearance, he was convinced, was sabotaged “by someone using a helicopter.” (In fact it was nothing more than a defective relay, that show’s presenter told me.)

Kaysing also tried to sue the makers of Capricorn One, the 1978 film about a fake manned Mars landing marketed with the tagline “Would you be shocked to find out that the greatest moment of our recent history may not have happened at all?” The film may have owed a debt to We Never Went to the Moon, but unfortunately for Kaysing’s lawsuit, the earliest version of the screenplay predated his notoriety and he lost the suit.

Kaysing corresponded with doubters and disbelievers from around the world, many of whom offered their own alleged evidence. Eventually far more single-minded skeptics emerged, among them Ralph René, who wrote NASA Mooned America at Kaysing’s insistence, and Bart Sibrel, who saw the light after Kaysing’s appearance on People Are Talking and would make a name for himself as an ambusher of astronauts. (When Sibrel demanded that a 72-year-old Buzz Aldrin swear on the Bible the moon landing had taken place, Aldrin socked Sibrel in the jaw.) This was truly the lunatic fringe. A movement had begun.

In February 2001, Kaysing appeared with René and Sibrel on Fox’s Conspiracy Theory: Did We Land on the Moon? narrated by actor Mitch Pileggi of the The X-Files. (Five years earlier, the network had caused a stir with its own staged hoax, Alien Autopsy: Fact or Fiction?) It was clear whose side the show was on: Kaysing’s conjectural case was, as usual, given respectful, ample airtime, and the man himself was introduced with the inflated credentials of “engineer and analyst.” Again his arguments went unrefuted. The program was watched by 15 million viewers in the U.S. and covered not only in the Los Angeles Times and New York Post but the Sydney Morning Herald.

NASA’s response to the program was to issue a one-paragraph press release with the heading “Apollo: Yes, We Did.” Meanwhile, Fox representatives boasted to the Deseret News that American skepticism of the moon landing had more than tripled after the program aired. The network re-aired the special the following month. It’s currently available to watch on Netflix.

Kaysing died in Santa Barbara in 2005, at 82, owing to complications from an angioplasty operation. He had spent many of his last years helping to run a sanctuary for abandoned cats.

In the author’s dedication of his 1988 book, Bill Kaysing’s Freedom Encyclopedia, Kaysing notes that his wife, Ruth, thinks “that I have a messiah complex, that I want to save the world … and, as usual, she’s right. That’s really all I intended to do in the first and last place.”

Some argue that Kaysing achieved the exact opposite, causing serious and lasting detriment to science, reason, and education. “He was a monumental antiscientist, responsible in many ways for one of the most colossal wastes of time and effort in my memory,” the astronomer and writer Phil Plait wrote for Discover. “How much energy,” Plait challenged, “how much brain power, how much simple time has been wasted on this ridiculous claim?”

Did the moon landing conspiracy theory pave the way for the more poisonous and discord-sowing theories of today? The denizens of QAnon message boards sometimes evoke the tone of We Never Went to the Moon and share the determination to erode trust in the system. And they do so while apparently fancying themselves precisely as enlightened and freethinking as Kaysing did.

But today’s conspiracy theories resemble only the darkest, most murderous elements of Kaysing’s thesis. Next to online rumblings about 9/11, President Barack Obama’s birth certificate, Sandy Hook, crisis actors, and Pizzagate, the fantasy of a lunar hoax feels almost wondrous.

Bill Kaysing was the unlikeliest but most effective single conspiracy-monger of the 20th century. By any  measure, his was an enduring contribution to the pop culture of its time, a uniquely pervasive bit of imagination-sparking speculative fiction, and a sidebar in the larger story of our fixation on our celestial neighbor. Perhaps if he had stuck to his original fictive intentions, We Never Went to the Moon would be remembered as an inspired sci-fi fantasy with an actual point to impart instead of a mostly forgotten, epically odd footnote.

measure, his was an enduring contribution to the pop culture of its time, a uniquely pervasive bit of imagination-sparking speculative fiction, and a sidebar in the larger story of our fixation on our celestial neighbor. Perhaps if he had stuck to his original fictive intentions, We Never Went to the Moon would be remembered as an inspired sci-fi fantasy with an actual point to impart instead of a mostly forgotten, epically odd footnote.

Speaking at Rice Stadium on Sept. 12, 1962, President John F. Kennedy promised that America would set out on “the greatest adventure on which man has ever embarked” before the decade was through. During his address, he spoke of the very ideals to which Bill Kaysing committed his life: boldness, understanding, and a hope for peace and the good of all men.

Humankind would go to the moon, Kennedy said. It would be an achievement that defied belief.